The strange case of the “0-kilometer used car” reveals a sophisticated strategy of rule arbitrage that poses a new kind of challenge to global markets.

On a dusty lot in Khorgos, the sprawling dry port on the China-Kazakhstan border, a strange ritual of modern commerce unfolds daily. A brand-new, gleaming Chinese electric vehicle, its protective plastic still on the seats and its odometer reading close to zero, is officially classified, documented, and sold as “used.” A few thousand kilometers away, in the bustling auto trading zones of Dubai, the same scene repeats. These are not isolated incidents; they are the visible nodes of a multi-billion dollar “grey” export chain that is channeling a torrent of Chinese cars to the world, often at prices slashing as much as 30% off their official counterparts.

This phenomenon, recently lamented by Great Wall Motor’s chairman Wei Jianjun as a “strange industry quirk,” has left many observers perplexed. Why would a manufacturer, or at least its ecosystem, go to such lengths to re-label a new product as old? Is this just another form of dumping, a desperate measure in a brutally competitive domestic market?

The answer is far more complex and consequential. This is not simply a market distortion. It is the signature of a powerful new form of Chinese commercial strategy, one we can call System Arbitrage. It represents a profound evolutionary leap from the country’s famed “Shanzhai,” or copycat, model of the past. The new playbook is no longer about hacking a product; it is about hacking the entire system of commerce, law, and regulation. And in doing so, it presents a novel and more elusive challenge to global competitors and the established rules of international trade.

Anatomy of a System Hack

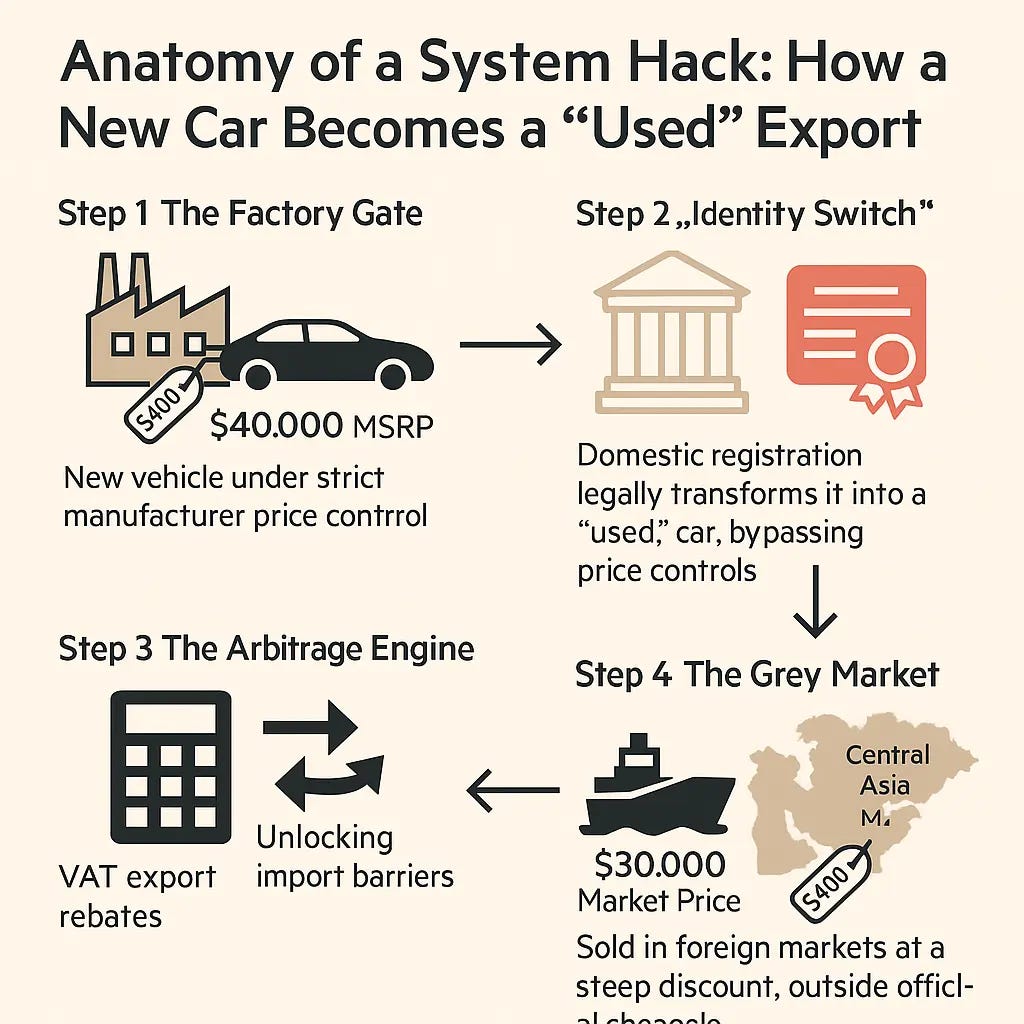

To understand the ingenuity of this model, one must dissect the alchemy that transforms a new car into a “used” one. This is not a crude deception but a precision-engineered process of exploiting the seams and frictions between different regulatory and commercial systems. It is a three-act play of arbitrage.

First comes the Domestic Legal Hack. In China, automakers exercise tight control over new car pricing through their official dealership networks to protect brand value and margins. This is a rigid, high-friction system. However, the moment a new car is registered with a domestic license plate—even for a single day—its legal identity transforms. It ceases to be a “new vehicle” and becomes a “used vehicle.” This simple, legal act serves as a key, instantly unlocking the car from the manufacturer’s price-controlled world and moving it into the far more flexible and unregulated open market for second-hand goods. The inventory is now liquid.

Second is the National Policy Hack. This change in legal status triggers a crucial financial benefit. In a bid to boost exports, the Chinese government offers significant value-added tax (VAT) rebates on the export of used vehicles. For a new car, this channel is unavailable. By performing the legal sleight of hand, these exporters—often nimble, independent trading companies—can tap into a stream of government-backed cash incentives, effectively creating a profit margin out of thin air that was never intended for brand-new products.

Finally, there is the International Trade Hack. Many countries, particularly in Central Asia, the Middle East, and Russia, have stringent requirements for the import of new vehicles. These often include the necessity of an official, manufacturer-authorized dealer network for sales, service, and warranties, creating a formidable barrier to entry. Used cars, however, frequently face a much lower regulatory bar. They can be imported by independent dealers or even individuals, bypassing the entire framework of official channels. The “0-kilometer used car” thus becomes a Trojan horse, allowing Chinese auto brands to penetrate new markets with incredible speed and at a fraction of the cost of establishing a formal presence.

Viewed together, this is not mere opportunism. It is a sophisticated piece of financial and logistical engineering. The masterminds of this trade operate not just as car dealers, but as connoisseurs of regulatory loopholes. Their battlefield is not the showroom floor, but the complex intersection of domestic transport law, national tax policy, and international customs codes. They have won, for now, by understanding the system’s code better than its creators.

The Evolutionary Leap: From Shanzhai to Arbitrage

To grasp the significance of this shift, one must place it in its historical context. For years, the dominant paradigm for understanding Chinese commercial innovation was “Shanzhai.”

Shanzhai 1.0, which peaked in the 2000s with the knock-off mobile phones of Shenzhen’s Huaqiangbei electronics market, was fundamentally about hacking the product. It was a mastery of the physical world. Its practitioners deconstructed iPhones and Nokias, reverse-engineered their components, and reassembled them with locally-sourced parts and features tailored to specific low-end market needs, like dual-SIM slots and booming speakers. The core competency was supply chain management and rapid, low-cost manufacturing. Its battleground was the factory floor.

Arbitrage 2.0, as exemplified by the 0-kilometer car, is about hacking the system. It is a mastery of the abstract world of rules. It doesn’t seek to re-engineer a physical product; the car itself remains untouched. Instead, it re-engineers the car’s identity as it traverses legal and financial jurisdictions. The core competency is navigating informational and regulatory asymmetry. Its battleground is the lawyer’s office, the accountant’s firm, and the bonded warehouse.

What drove this evolution? The answer lies in the immense pressure cooker of China’s domestic economy. Shanzhai 1.0 was born from China’s strength as the “world’s factory”—an abundance of manufacturing capacity. Arbitrage 2.0 is born from a newer, more painful reality: crippling overcapacity and a state of hyper-competition, often referred to domestically as neijuan(involution). China’s auto industry can now produce nearly twice as many cars as it can sell at home. This has ignited a vicious price war and a frantic race to innovate, where new models become obsolete in months, not years.

In this environment, unsold inventory is not just a line on a balance sheet; it is a rapidly depreciating asset, a ticking financial bomb. The System Arbitrage model emerged as a brilliant, if unorthodox, pressure-release valve. It provides a highly efficient, off-the-books mechanism to clear that excess inventory, convert it to cash, and propel it overseas, all while bypassing the brand’s own carefully constructed (and slow-moving) official channels.

The Global Implications: A New Competitive Threat?

For multinational corporations and global policymakers, this new model presents a challenge that is far more complex than competing with a cheaper product.

First, it represents a form of asymmetric commercial warfare. Western and other established automakers operate as “regular armies.” They are bound by strict rules of engagement: dealer agreements, brand consistency, ESG commitments, and a deep-seated culture of regulatory compliance. The Chinese system arbitragers operate as a “guerrilla force.” They are nimble, decentralized, and unburdened by such constraints. They exploit the very rules that bind their larger competitors, turning their opponents’ strengths—structure, process, and predictability—into vulnerabilities.

This approach marks a crucial divergence from previous Asian export miracles. When Japanese automakers conquered the world in the 1970s and 80s, they did so largely by playing within the existing global trade system and winning on its terms. Their victory was based on superior manufacturing processes (Lean Production) and product quality. The new Chinese model, in contrast, achieves its competitive edge partly by operating at the very margins of that system, or by creating parallel pathways that circumvent it entirely.

The most profound danger, however, may be to China’s own long-term ambitions. The strategy is a double-edged sword, potentially leading to a cannibalization of its own future. As brands like BYD, Geely, and Great Wall invest billions to build official overseas sales networks and cultivate a premium brand image, the grey market arbitragers follow in their wake, undercutting official dealers and sowing price chaos. This creates a classic “prisoner’s dilemma,” where the short-term benefit of clearing inventory for one set of actors actively undermines the long-term brand equity of the entire national project. The consumer in Moscow or Riyadh who buys a grey-market Chinese EV may get a bargain, but with no official warranty, no software support, and no service network, their first experience with a Chinese auto brand could easily be their last.

At a macro level, this phenomenon introduces systemic risk for global trade. It distorts market data, making it difficult to track true sales and market share. It creates unpredictable price volatility and risks triggering a harsh protectionist backlash from destination countries, who may feel their regulatory frameworks are being gamed. It challenges the foundational premise of the WTO-led order: that trade should be transparent, predictable, and based on a common set of rules.

Conclusion: From System Hacker to System Architect

The emergence of the System Arbitrage model is a testament to the incredible dynamism and adaptive intelligence within China’s commercial ecosystem. It demonstrates a level of strategic thinking that moves far beyond the factory floor into the very “code” of global capitalism. In the great game of global commerce, Chinese firms have proven they are now among the world’s most sophisticated and formidable Game Players.

But this path, for all its cleverness, is a shortcut, not a highway. It is a strategy for a challenger, not a leader. True and sustainable global leadership is not built on exploiting the loopholes in the existing system. It is built on the far more difficult task of creating new systems, setting new standards, and, most importantly, earning the trust required to make those systems work for everyone.

The world is watching this evolution with a mixture of awe and apprehension. The key question now is whether China can make its next, and most critical, evolutionary leap. Can it transition from being the world’s most ingenious System Hacker to becoming a responsible and trusted System Architect? The answer will not only determine the fate of its own global champions but will also play a decisive role in shaping the international commercial order of the 21st century.