China’s Generative AI: Building Innovation Through Regulation

While the U.S. deregulates and the EU tightens compliance, China turns approval into infrastructure for industrial adoption.

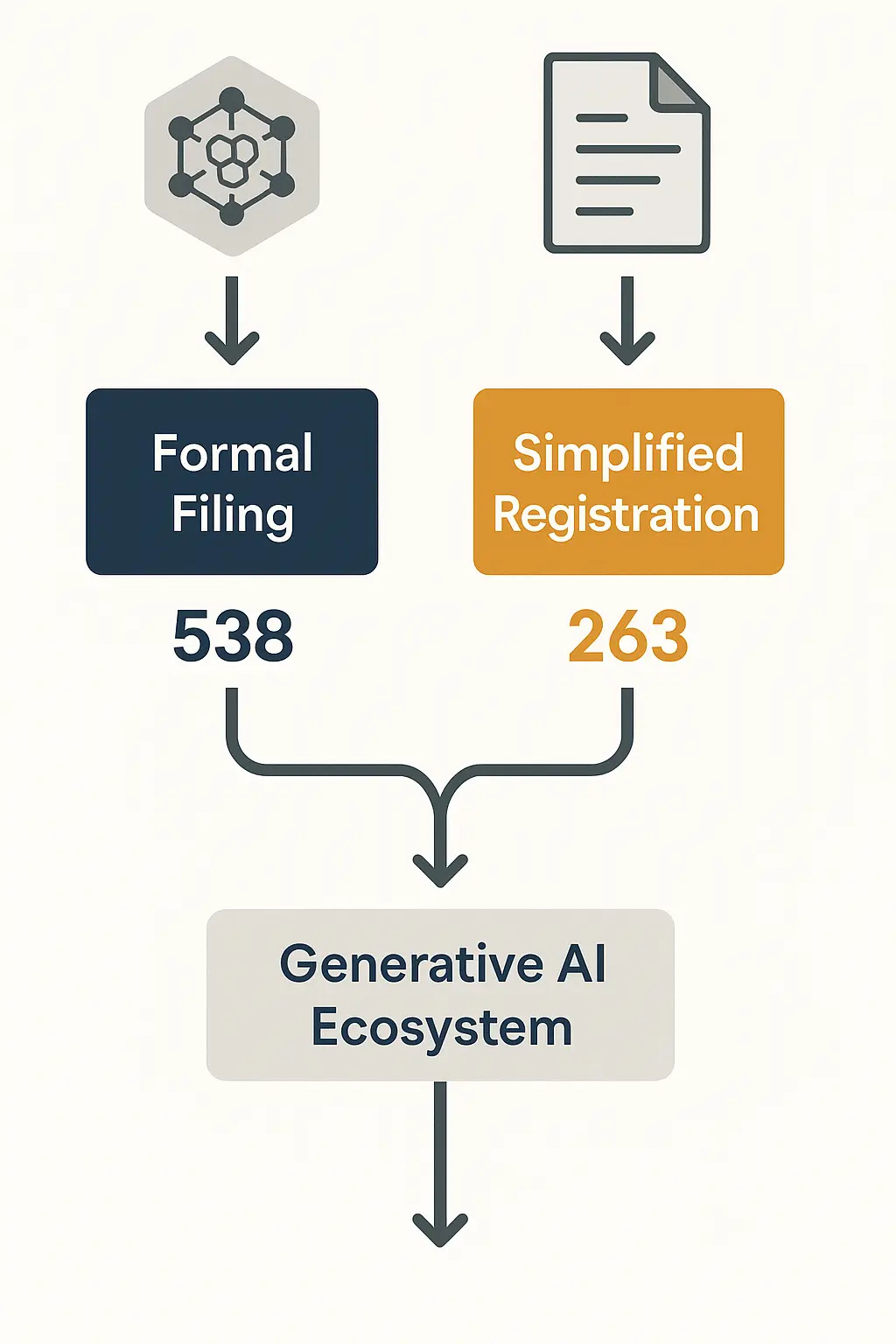

As generative AI reshapes global technology landscapes, different regions are pursuing fundamentally different approaches to development and governance. By August 31, 2025, China’s Cyberspace Administration had processed 538 generative AI service filings and 263 application registrations, totaling 801 officially approved AI services and revealing a systematic approach that contrasts sharply with regulatory developments in the United States and Europe.

While the Trump administration’s July 2025 “America’s AI Action Plan” emphasizes deregulation and market-driven innovation, and the EU’s AI Act implements risk-based compliance requirements, China has constructed a two-tier filing system that treats regulatory approval as developmental infrastructure. These divergent approaches offer insights into how major economies are balancing innovation with oversight in the AI era.

How Three Superpowers Are Playing Different AI Games

The global AI regulatory landscape in 2025 reveals three distinct approaches to managing generative AI development.

The United States has shifted toward deregulation. Following President Trump’s January 2025 executive order revoking Biden-era AI oversight measures, the administration released its AI Action Plan in July 2025, focusing on “removing barriers to American AI innovation” and establishing “American AI as the gold standard worldwide.” The plan emphasizes reducing federal regulations, expediting data center permits, and promoting private sector adoption with minimal government oversight.

The European Union implements comprehensive risk-based regulation. The EU AI Act, which took effect in August 2024, applies a graduated approach with specific compliance deadlines. Prohibited AI systems became banned in February 2025, general-purpose AI model obligations took effect in August 2025, and full implementation will occur by August 2026. The framework emphasizes safety, fundamental rights protection, and harmonized standards across member states.

China operates a filing and registration system.Rather than reactive regulation or market-driven development, China has built a predictable approval pathway where regulatory compliance enables rather than constrains innovation. This system distinguishes between base models (requiring formal filing) and applications built on approved models (requiring only registration).

China’s Two-Tier System: Filing vs. Registration

China’s regulatory framework creates clear development pathways through its binary approach to AI oversight. According to official records through August 2025, this system has processed 538 base model filings and 263 application registrations.

Base models require formal filing approval for foundation models involving training or fine-tuning capabilities. This includes large language models, multimodal systems, and other foundational AI capabilities. The filing process involves more stringent review but, once approved, enables downstream development.

Applications built on approved models need only registration, a streamlined process that has accelerated deployment. Companies can launch multiple AI-powered services once their underlying models receive filing approval, creating what amounts to a regulatory API for AI development.

This system has practical implications: Shanghai-based companies alone registered 96 different applications in the period covered by the data, many building on previously approved base models from major players like Baidu, Alibaba, and ByteDance. The predictability allows companies to plan AI strategies around known regulatory timelines rather than uncertain approval processes.

However, this approach also raises questions about innovation constraints and the balance between systematic oversight and technological flexibility that other regions handle differently.

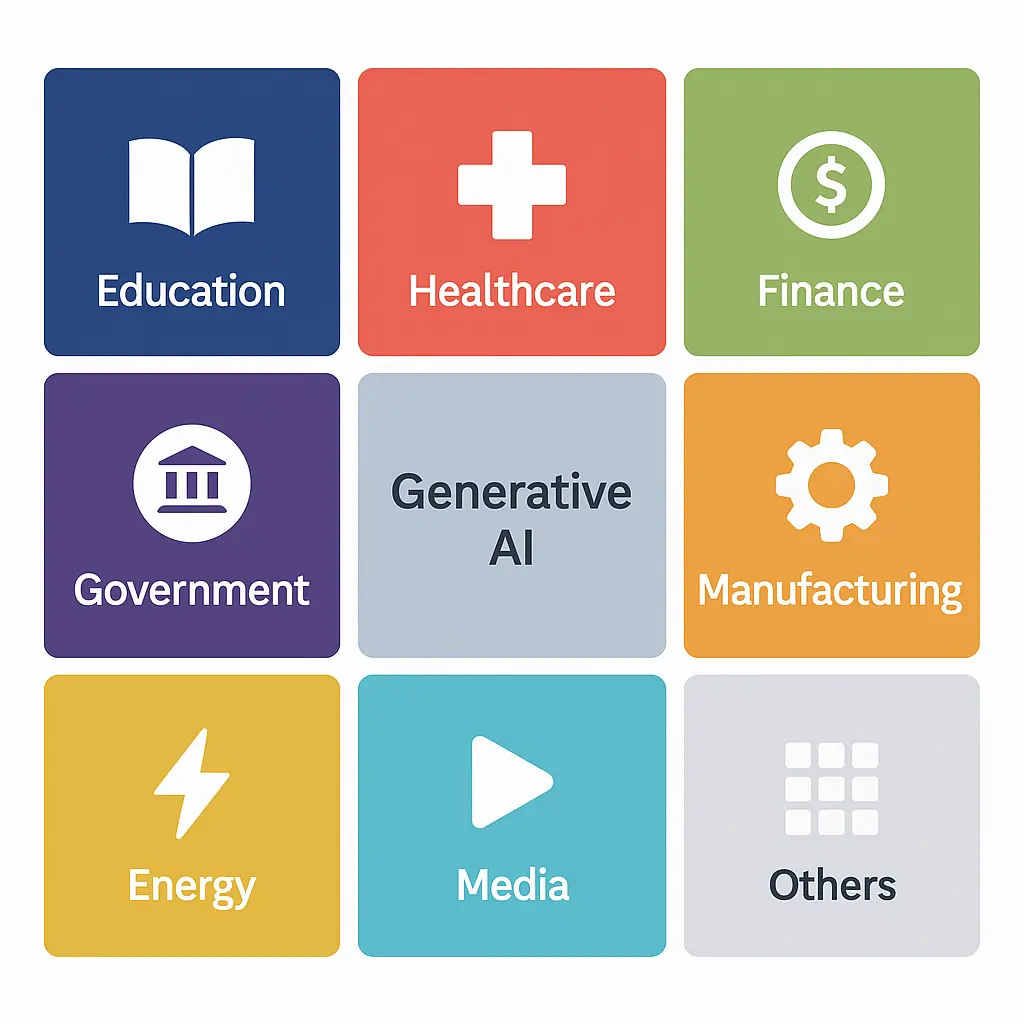

Why China’s AI Isn’t Chasing Consumer Fantasies

China’s filing data reveals a pronounced emphasis on industrial and institutional applications rather than consumer-facing AI services. This contrasts with development patterns in other major markets.

Education represents the largest category, with dozens of models designed for tutoring, language practice, and exam preparation. Companies like Gao Deng Education Publishing House filed education-specific models, while provincial education authorities registered AI teaching assistants. This aligns with China’s educational policy priorities but also reflects institutional rather than market-driven demand.

Healthcare and financial applications proliferate throughout the records, from AI medical assistants deployed in hospitals to compliance and customer service systems in banks and securities firms. China Industrial and Commercial Bank alone registered multiple AI services, indicating integration into high-stakes, regulated environments.

Government and public sector applications appear frequently, with models for drug supervision, judicial processes, and administrative services. This suggests AI development priorities that align with state institutional needs rather than purely commercial applications.

This industrial focus differs from the consumer-oriented AI development more common in Silicon Valley, where applications often target entertainment, creativity, and personal productivity before moving into institutional use.

The Hardware-First Strategy That Changes Everything

Chinese companies demonstrate a distinctive approach to AI deployment through hardware integration rather than cloud-first architectures. The filing records show significant investment in on-device AI capabilities.

Xiaomi secured multiple approvals for AI models designed for edge deployment, including “Xiaomi Surge AI Perception” models for image processing and “Xiaomi Surge Sensing” systems. These represent on-device capabilities rather than cloud services.

Beijing Zhiyuan Research Institute (BAAI) filed multiple “Emu” models for text-to-image and text-to-video generation specifically designed for local processing. The emphasis on multimodal capabilities suggests comprehensive device-based intelligence rather than single-purpose tools.

This hardware-anchored approach potentially reduces dependence on cloud infrastructure and could influence global markets as Chinese manufacturers export devices with embedded AI capabilities. However, it also raises questions about performance limitations, privacy implications, and the trade-offs between local processing and cloud-based capabilities.

Beijing vs. Shanghai: The Tale of Two AI Cities

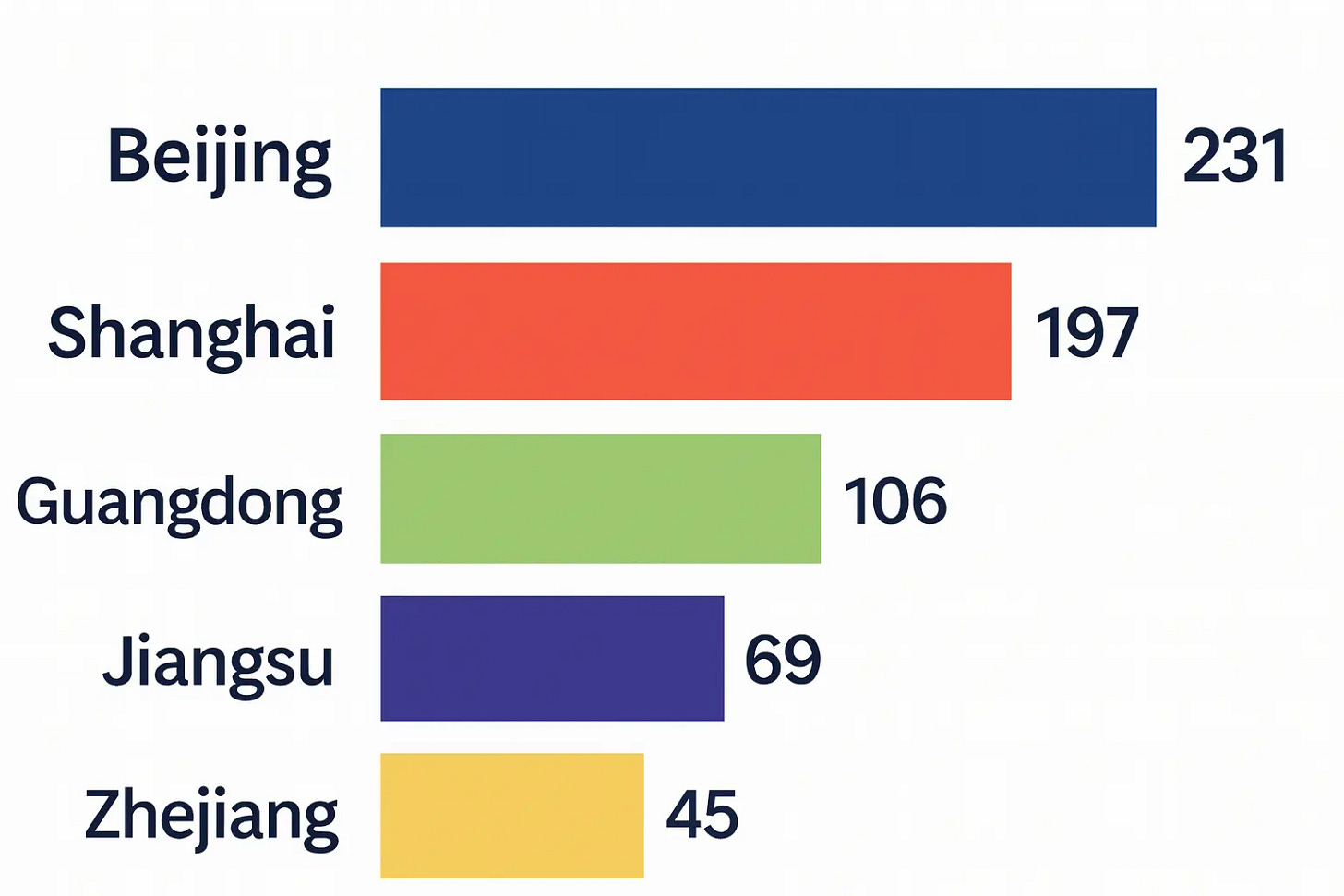

The geographic spread of AI filings reveals both concentration in major hubs and meaningful distribution across China’s economic regions.

Beijing leads with 231 filings, representing nearly 29% of the total and concentrated in fundamental AI capabilities and government-related applications. The capital hosts models for judicial processes, national archives, and administrative operations, reflecting its role in state-directed development and regulatory oversight.

Shanghai follows with 197 filings, accounting for about 25% of the total and focusing on commercial applications including tourism, media, business services, and financial applications. This reflects the city’s traditional role as China’s commercial and financial center.

Guangdong contributes 106 filings, representing 13% of the total, with strengths in manufacturing, hardware integration, and consumer applications. Jiangsu adds 69 filings (9% of total) and Zhejiang contributes 45 filings (6% of total), both bringing industrial expertise and regional innovation capacity.

The remaining 153 filings (19%) are distributed across other provinces and regions, creating a more geographically diverse ecosystem than might be expected from China’s traditional innovation centers.

This distribution shows both concentration advantages–with Beijing and Shanghai accounting for over half of all filings–and meaningful regional participation across China’s major economic zones. The pattern suggests a hybrid model combining hub-based coordination with distributed implementation capacity.

When Everyone Gets to Play: SOEs, Giants, and Startups

China’s AI development involves multiple organizational types operating simultaneously, creating both diversity and potential redundancy.

State-owned enterprises lead critical infrastructure applications. China National Petroleum Corporation filed the “Kunlun Large Model” and State Grid Corporation developed energy sector AI systems, ensuring AI capabilities in strategic industries regardless of market dynamics.

Technology giants (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, ByteDance) provide foundation layers through general-purpose and multimodal models. Baidu’s “Qianfan” platform, Alibaba’s “Tongyi Qianwen” series, and ByteDance’s “Doubao” models serve as infrastructure for smaller companies.

Startups and emerging companies drive vertical specialization. Companies like Beijing Moonshot AI, Shanghai MiniMax, and numerous AI-focused startups contribute models tailored to specific industries or use cases.

Universities and research institutions provide open-source frameworks and domain-specific capabilities, with institutions like Tsinghua University, Shanghai AI Lab, and Beijing AI Research Institute contributing both research and practical applications.

This plurality differs from venture capital-driven ecosystems or government-led research approaches, creating resilience through diversity but potentially also inefficiencies through overlap.

What This Means for the Global AI Race

China’s systematic approach to AI development operates within a rapidly evolving global landscape where major economies pursue different strategies.

Regulatory philosophy differences are becoming apparent. The U.S. emphasizes market freedom and competitive advantage, the EU prioritizes safety and rights protection, while China focuses on systematic integration with institutional priorities. Each approach involves trade-offs between innovation speed, safety assurance, and alignment with societal goals.

International competitiveness questions arise from these different models. China’s industrial-first approach may create advantages in regulated sectors, while potentially lagging in consumer innovation. The U.S. market-driven model may generate rapid consumer adoption while facing institutional implementation challenges. The EU’s rights-focused approach may ensure safety while potentially constraining development speed.

Technology transfer and standards implications emerge as each system develops different capabilities and approaches. Chinese hardware-embedded AI, American cloud-based services, and European rights-compliant systems may create fragmented global markets or require significant adaptation for international deployment.

The Verdict: Three Paths, No Clear Winner Yet

China’s generative AI development through August 2025 demonstrates a systematic approach that prioritizes institutional integration over market-driven adoption. The filing and registration system creates predictable pathways for development, though at potential costs in terms of innovation flexibility. Industrial applications receive priority over consumer services, possibly ensuring AI capabilities in critical sectors while potentially limiting creative applications.

The hardware integration emphasis may reduce cloud dependencies and create export opportunities, but also raises questions about performance trade-offs and global compatibility. Geographic distribution across multiple centers creates resilience but may lack the concentrated advantages of single-hub development.

Comparing these approaches across the U.S., EU, and China reveals different assumptions about optimal AI development strategies. The U.S. emphasizes market efficiency, the EU prioritizes safety and rights, while China focuses on systematic institutional integration. Each model offers advantages and faces limitations.

The coming years will provide evidence about which approaches prove most effective for deploying AI capabilities that benefit economic development and social needs. Rather than a single optimal model, different regulatory and development approaches may suit different economic systems and social priorities.

The question for global observers is not which model is superior, but how these different approaches will interact, compete, and potentially learn from each other as AI technologies continue evolving rapidly across all major economies.

About Hello China Tech

I’m Poe Zhao, and I bridge the gap between China’s rapidly evolving tech ecosystem and the global community. Through Hello China Tech, I provide twice-weekly analysis that goes beyond headlines to examine the strategic implications of China’s technological advancement.

Found this useful?

→ Share this newsletter with colleagues who need to understand China’s tech impact

→ Subscribe for free to receive every analysis:

→ Follow the conversation on 𝕏 for daily updates and additional insights

Get in touch: Have questions about China’s tech sector or suggestions for future analysis? Reply to this email – I read every message.

Good piece, particularly on the industrial integration side. One note I'd add is that the Chinese regulatory approach looks pretty coherent at the moment, but it's also one that has evolved a lot as regulators partly stumbled (or were forced into) more pro-development practices.

Many of the biggest changes came between the draft and final versions of the Gen AI regulation (such as excluding R&D and all non-"public facing" gen AI uses from regulation - thus pushing people towards industrial applications), but even after that the CAC's approach to regulatory approvals evolved a ton. In the early months after the reg went into affect (fall 2023), they only accepted a handful of registrations/备案, making this a de-facto (and pretty strict) licensing regime. You had companies waiting through several months of uncertainty for approval to launch in China, actually leading them to launch first overseas first while they waited.

But over the course of 2024 and especially into 2025, the CAC appears to have steadily eased up on the companies. Some people say the former "licensing" vibe has turned more into what a 备案 is actually supposed to be in the first place: registration.

Those changes appear to be due to a variety of factors.

- enduring economic challenges (meaning pressure to ease up on companies, "宏观政策取向" has changed)

- greater standardization/roadmaps for the companies to follow (such as 网安标委‘s “生成式人工智能安全基本要求" standards)

- companies just getting better at content control

- regulators just getting more comfortable with the technology and their ability to intervene with the companies when needed (a lot like the evolution of internet content management 2013-2015).

Anyway, that's a long-winded way of saying that while I think China/CAC has landed in a pretty effective place, but this was as much due to wider political/economic/technological circumstances as to a well thought through regulatory philosophy. But hey, that's probably the reality just about anywhere...